Assessment Technology in The Age of Hypercompetition (Point of View Paper)

As markets heat up all over the world, companies strive to end with today's dynamic conditions, or at least survive them. "Hypercompetition is an environment of intense change in which flexible, aggressive, innovative competitors move into markets easily and rapidly, eroding the advantages of the large and established players."

Responding to this fast-forward world of "the quick or the dead," companies have undertaken reinvention and the redesign of how they do business. They are casting all the industrial age rules, assumptions, and hierarchical trappings on the table to be changed, tossed out, or revitalized. All of this in an effort to streamline processes that serve and add value to the customer. Management has become captivated by strategies of radical process redesign and, in some cases, has taken into account only as an afterthought the skills and capabilities of those who must ultimately manage and be responsible for the performance of the redefined organization.

What will employees need to know to successfully execute the new process? What training of existing employees or hiring of new people will be required to change the organization to one that operates with speed, resiliency, and innovation? How do you anticipate what skills your organization will need in the future, and how do you select and develop employees based on those needs?

Without the right answers to these questions, reengineering efforts fail or, at least, fall markedly short of their promise. James Champy, coauthor of Reengineering the Corporation: A Manifesto for Business Revolution, said recently, "When I wrote about reengineering, I didn't mean to suggest that you fire half the people and expect the other half to do twice the work."

In fact, the ability to tie human capabilities precisely and comprehensively to business strategies will be the next frontier of competitive engagement. This issue will ring loud in the halls of reengineered corporations seeking to continue on. Having the right people, with the right skills, in the right (reengineered) job (or process) will mean the difference in an unforgiving marketplace.

"Consider the case of Seymour Cray," says Donald Curtis, a partner in the accounting firm of Deloitte & Touche, in his 1990 book Management Rediscovered. "Cray was the top engineer and visionary for Control Data, the Fortune 500 company that was once the only manufacturer of supercomputers. Disgruntled by the company's reluctance to pursue one of his projects, he left one day with some other Control Data engineers to form Cray Research. Assuming that no major financial transactions took place that day, the accounting system recorded that nothing happened. But that defection marked the beginning of a spiraling decline for Control Data, which no longer makes supercomputers."

Investing in acquiring, keeping, and developing the right people with the right skills for today is no less than an investment in the continuation of corporate existence. Today, with decisions, accountability, and responsibility for customer satisfaction being pushed down into the organization (well below the level of the Seymour Cray's of the past), the skills and capabilities of employees on the front lines, charged as they are with the success of the enterprise, are as critical an asset as any the company retains.

THOSE WHO REMAIN

What are the new core skills and competencies required of these employees? If roles have been redefined, how do employees know what is expected of them? Who is qualified for the newly defined positions, and how is it determined who will remain?

The employees who have remained after reorganization, downsizing, or reengineering are survivors, frequently with a "survivor" mentality. They have the skills and competencies that, it has been determined by some process, will carry the company into the future. But many of these remaining employees are on permanent overload, operating with increased speed in new and unfamiliar terrain, doing more with a great deal less. Are they, in fact, the right people for the company's new direction? Was the process used to retain these employees designed to identify the skills and capabilities needed in the organization's newly envisioned future?

These surviving employees are also working in a transition period where, unlike in the past, there are no corporate promises of future employment. Even being good at their job is no defense against sudden unemployment. The protective good will and trust of the past is almost gone. Companies may have secured a stronger financial position, but not without cost to employee morale, which in some companies is nearly bankrupt. As a result, corporations are only now beginning to understand the impact of discarding the psychological connection that once existed between companies and their employees. They recognize the need to change the corporate culture from one of employee loyalty (and perhaps dependence) to one that today fosters resiliency, adaptability, and independence.

After an employee leaves for another opportunity, what are the business issues associated with a position or function? How critical is the nature of the position? Is there high turnover in that job?

THE ROLE OF VALUES IN ALIGNMENT OF THE EXTENDED ENTERPRISE

What are the values employees must embrace to be successful in an organization? How do you hire and train people in a way that supports and actualizes those values? If the game has changed, can a company hire and/or train to achieve a new culture?

Often after downsizing, many companies have benefitted from outsourcing. According to a recent study published by the Outsourcing Institute, on average, companies have seen a 9 percent cost savings and a 15 percent increase in capacity and quality with outsourcing. In fact, experts these days are predicting that in the future there will be a minimum skeleton crew of full-time employees and that companies will be comprised of individual and organizational alliances that come together and disband based on market conditions. In this initial stage, however, many companies fear the use of multiple outside resources, even with all the upside advantages, because the chilling downside is that it may breed strong, opportunistic competitors. Also problematic with the use of part-time and temporary employees is the company's inability to ensure their alignment with the company mission and the brand.

Today, it is critical for companies to hire people who share their values and can effectively reflect their brand. Creating alignment on values, essentially hiring and developing people who are able to reflect what the company stands for, is far more difficult with an extended enterprise. This enterprise may have temporary, part-time, or external employees; it may have a global workforce, one that may have complex alliances and distribution channels. It can, however, be done. Consider the original and innovative approaches of Saturn, for example, that harnessed the power of a renewed corporate culture and competitively advanced the organization.

The traditional approaches to selecting and developing people were once grounded in a known range of skill sets and predictable performance.

RE-EVALUATING HOW THE WORK GETS DONE

After an employee leaves for another opportunity, what are the business issues associated with a position or function? How critical is the nature of the position? Is there high turnover in that job? What is the need to improve or change performance in the position? And what will be the future competencies and responsibilities required of that position? Should the employee be replaced at all?

Companies are also finding that after downsizing, some of the key remaining people are leaving for new opportunities. The response to this loss in the past would have been to immediately hire a replacement whose skills closely resembled those of the successful employee who left. But today, the loss of a key employee typically summons a more complex response.

First, the question arises, why did he or she leave? If the company wanted him or her to remain, what could the organization have done differently? Second, when an employee leaves it changes more than just who occupies a position, it changes how the work is performed. Third, employees normally participate in groups and teams and have informal strategies and tactics to get the job done, most of which does not appear anywhere on paper within the company. It is often these undocumented behaviors, attributes, methods, interactions, and personal objectives of the departed employee that get the real work done. These informal processes are rarely understood, let alone formalized and replicated to the organization's gain. So, instead of immediately being filled, that vacancy represents an opportunity to re-evaluate and alter how the work is done. Perhaps it will be determined that it is better to go outside the company to provide the service once performed by the employee. In any case, changes in personnel today can have far more impact than in the hierarchical, loaded-with-redundancy organizations of the past.

HIRING FOR NEW IDEAS—THE GLASS BREAKERS

Does the company have current information about competencies, tasks, skills, roles, and responsibilities required of positions? How will the job requirements change in the next few years? What does this mean with regard to hiring decisions?

The traditional approaches to selecting and developing people were once grounded in a known range of skill sets and predictable performance. Today there are important new competencies and work orientation factors emerging. The success of the new enterprise is dependent upon, for instance, operating accurately and independently with speed, utilizing flexible thinking, and handling change with resilience and energy. In Tom Peter's new book In Search of Wow, he discusses the need companies have for people with experiences outside the norm, whose résumés do not resemble the standard career development path, but who can contribute in ways that are new and innovative.

The CEO of Wilson Learning captured the attention of CEOs and senior-level executives when in a presentation on reengineering, he posed the question, "So after downsizing, reorganizing, and rightsizing, how many glass breakers do you have left in your company?" He was referring to those bright, creative, innovative people who are hard to manage. They are the questioners, the outsiders, the troublemakers, and they are usually the first to be laid off. They are also the people with new ideas and new approaches, who think in ways unlike anyone else and who can change an entire industry. How do organizations (inclined as they are toward stability and conformity) set consistent, fair performance standards for all employees and at the same time make room for unique, imaginative people and their ingenious ideas?

THE COST OF NOT USING ASSESSMENT TECHNOLOGY

Why do companies need state-of-the-art assessment technology? What issues arise that keep them from utilizing valid, effective methods to hire, promote, and develop a workforce that can meet the competitive challenges they face? Underlying the formidable business challenges discussed so far is the need to hire, as well as retain and develop, the right people, with the right skills, at the right time. Why have so many organizations not used the state-of-the-art assessment technology available today? Senior management and those responsible for hiring and development decisions often believe that the best of these technologies are too expensive, take too long to render results, and are unnecessarily cumbersome and labor intensive.

COST, TIME, AND LABOR

Cost is relative. The cost of assessment technology is not expensive when compared to the cost of bad decisions, poor skill performance, and employees not operating in alignment with the company's strategy. Speed can be achieved through advanced technology including, for example, on-site assessment. The issue of labor intensiveness only arises when time is wasted, and there is no payoff for whatever time is invested.

It is important today to explore the latest assessment and measurement tools and to consider the cost of the mistakes that can result from not using the technology. Take, for example, the case of a specialized publishing company that after years of hiring and developing salespeople, set out to examine the cost of a bad hiring decision in their sales division. They were shocked to discover that including salary, benefits, training, and severance, the cost of hiring and developing the wrong salesperson, over an 18 month period (the time it took for their salespeople to become productive or not), was nearly $250,000.

In another case involving a large engineering company, the firm brought a new, entry-level employee on board. Everyone involved in the hiring decision felt the candidate was perfect for the company. Unfortunately, one applicant for that position claimed the hiring process was unfair and inconsistent. Further, he claimed the testing for the position, while exact and demanding, was irrelevant to the real requirements of the job. The lawsuit was settled out of court, at a high cost to the firm in both dollars and bad publicity. In light of these companies' experiences, reliance on industrial age approaches in the information age is neither a good business nor a sound financial decision.

Today, speed is essential. Frequently, companies decide against using the most modern assessment approaches because of the time involved. But new levels of speed have been achieved, and it is speed beyond just compressing the traditional assessment process. The speed comes through the use of computers doing what computers do best (compiling data, merging files, running numbers, etc.), allowing the people in the assessment process to devote their time to doing what people do best—observe, make judgments, and provide detailed feedback.

Assessment technology can provide the tools to accurately and powerfully translate corporate strategy into action.

In addition, new technology in the assessment process can pinpoint the correct training and development interventions given various assessment results. It can provide the solid data-based foundation for the redesign of new jobs. It can match skills to jobs and people to positions in ways that eliminate long and confusing learning curves that may or may not produce results. The truth is, companies no longer have time for guesswork, gut-level hunches, and "informed" subjective approaches to the hiring and developing of their people.

The issue commonly is raised that even the best and most modern assessment technology is labor intensive. There is, of course, a balance between involvement and value achieved. If the involvement of management is high, there must be a corresponding result of high quality, high accuracy, and high value to make the effort worthwhile. This must be built into any selection or measurement process. Even with the advancements that have come along in the assessment world given the new computer-assisted approaches, high quality, high accuracy, and high value do not come without an organization's commitment and effort.

TRANSFORMATION THROUGH ASSESSMENT TECHNOLOGY—CASE STUDIES

How does today's assessment technology offer tangible solutions to the business issues of reengineering, changing values and culture, and identification of core competencies of today's employees?

MODELING THE FUTURE OF BANKING

Assessment technology can provide the tools to accurately and powerfully translate corporate strategy into action. For example, a large global bank was changing its strategy within one of its Asia Pacific country operations. Its new strategy focused on increasing customer satisfaction and increased business. A "greenfield approach" (starting over) was used to translate the strategy and model the future of banking. In looking at its 70,000 employees and existing skill sets, the bank realized the major challenge it had to face was which employees, both managerial and front line, had the skills it needed?

As the bank analyzed critical success factors, it realized that very few employees had all of the required skills. The challenge became how to determine those employees who had the greatest skill match to the new positions and what their new training and development requirements would be.

This information was then used to establish training priorities for new appointees, which resulted in people getting the high priority training they needed.

Wilson Learning conducted a complete job analysis. This included a major "futuring" input from a number of subject matter experts from both inside and outside the bank. Based on competency models, Wilson Learning built a number of different types of behavioral-based assessment tools. These tools included one-day assessment centers for three levels of managers, video-based electronic assessment systems for frontline sales and customer service personnel, and an audio-based electronic assessment system for transaction processing employees.

As the strategy was implemented into a new region, all jobs were announced to be vacant. All existing employees and managers were encouraged to apply/reapply for those jobs they felt they were best suited for. Assessment activities were conducted and the reports became a major input into the selection decisions made to staff this new structure. Assessment reports were also constructed to give information about the development needs of each candidate. This information was then used to establish training priorities for new appointees, which resulted in people getting the high priority training they needed.

Senior managers from the bank acknowledged that the success of their reengineering effort was in large part due to the use of Wilson Learning's job futuring, selection, and measurement technology. The information helped them select and develop employees with the necessary knowledge, skills, and ability requirements to effectively execute the new processes.

MANUFACTURING PLANT REENGINEERED TO BE INDUSTRY BEST

A medium-sized manufacturing plant producing medical supplies and high-tech equipment was committed to a new planned direction with the goal of becoming industry best as determined by such sources as Industry Week magazine. The plant defined its strategic direction with the assistance of a computer-based group facilitation tool developed and conducted by Wilson Learning. The resulting strategy consisted of enhancing all workers' skills, empowering teams, changing processes, and increasing customer focus.

As a first step to enhancing workers’ skills, a complete training needs assessment was conducted by Wilson Learning for everyone in the organization. The purpose of this assessment was to determine the key competencies of all positions within the plant.

Wilson Learning created a custom competency model for all job families. Benchmarking teams reviewed the industry's top performers to determine the needed competency levels for achieving industry best status. The next stage was individual assessment and development planning.

The result of this process was a human resource development plan, completely focused on the organization's strategic vision.

Once the data was collected, Wilson Learning developed four types of customized reports. The first reports provided comprehensive overviews of the organization's or team's strengths and weaknesses in comparison to the planned direction. The reports also highlighted the skill and mind-set gaps that existed between the current world and the benchmark target. This information was used for generating organizational development plans. A second organizational report was used to evaluate the existing curriculum by identifying gaps and which training or other developmental activities were not useful in supporting the strategic direction. This report was used to revise and align the curriculum with their strategic goals.

At the individual level, reports developed by Wilson Learning showed personal strengths and weaknesses in comparison to the job function and industry best status. Course Guide reports gave a personally prioritized list of available developmental activities for each employee. Using a customized Action Planning Guide, employees developed a personal development plan to share with their manager. All managers, with the support of a Coaching Guide and results interpretation session, also prepared for their employees' developmental sessions. Each session ended with an agreed to development plan with specific training, designated mentors, and follow-up plans.

The result of this process was a human resource development plan, completely focused on the organization's strategic vision. New skills were identified and all development opportunities that did not support the vision were eliminated, freeing resources to address needed development. The organization determined the size of competency gaps between current and benchmarked performance and tracked them in order to see the major developmental needs. Everyone emerged from the planning meetings with an understanding of the company's strategic vision, how they personally were expected to contribute to that vision, and the development opportunities they had to address if the company was to achieve its goals. Managers were prepared to guide and coach their employees in developing the competencies critical to achieving the vision.

In essence, the organization brought together technology and strategy to align its human resource potential. The plant systematically developed employees' skills and capabilities and transformed itself into the best in its industry.

MOST LIKELY TO SUCCEED

In 1994, fully understanding the risks, North America's largest information organization that served the workers' compensation marketplace embarked on reengineering.

In 1992, the organization completed its corporate move to South Florida with the transfer of its senior management group. They then began transitioning their business and culture toward a fee-for-service environment. The goal was to complete this transition during 1995. The organization's leadership felt that the establishment of such an environment would be critical to its long-term survival. At the time, the organization had a head count of 1,368 with a skill mix of clerical, technical, managerial, actuarial, and systems employees.

The organization was typical of a company that had been through very little change since its inception (1922). It was bureaucratic, risk averse, conservative, process driven, unresponsive to customers, and funded by an assessment system to recoup its operating expenses. They knew that a key ingredient to success was a new method of selection for managers, team leaders, and team members who would be handling customer service. The newly envisioned organization would meet the needs of an expanding and changing customer base by building organizational power and creating a new infrastructure.

The first step in this process was to redefine the organization's mission and direction. Using a process embracing broad involvement from leadership, they revised their mission statement. They planned to literally reengineer the organization into becoming a provider of database products, software, publications, and consulting services.

To achieve this, the organization needed to develop a culture that was:

- Proactive

- Accepting of challenge and risk

- Collaborative

- Customer/market driven

- Flexible

- And, most important, revenue based

Today, the organization is well on its way to successfully completing its three-year transition and currently is an organization of 1,000 employees (85 percent professional). As part of this change, they identified job families in the reengineered organization. They sought to answer the questions, "What are the new job families?" and "What are the competencies in these new job families?"

One of the key challenges during this transition was to review the "regionalized field customer service" concept that had been in place for many years and find a way to make this effort much more customer focused, less costly, and centralized, while creating a team-based environment. They knew that a key ingredient to success was a new method of selection for managers, team leaders, and team members who would be handling customer service.

The organization also knew that the selection process needed to be linked to the competencies that were being identified for these customer service positions as part of the compensation effort.

As they talked about the new method of selection that would be required, the organization determined that an assessment process designed around the critical competencies of the team member position in the new customer service center would be most appropriate. The project team assembled for this study of the organization's customer service effort was comprised of individuals from the customer service operational groups, finance, systems, and human resources. The team felt that the new assessment process needed to:

- Provide the capability to test a large number of applicants

- Be computer-based and interactive

- Provide a realistic job preview

- Provide detailed feedback reports for both managers and candidates

- Be scored immediately so that test scores could be provided within 24 hours

Because of time restrictions, the assessment process needed to be designed within an eight-week period.

THE SELECTION PROCESS

After an initial review with representatives from the organization's customer service operational groups, Wilson Learning agreed to focus first on the assessment of the position of Team Member and to use as the foundation for that assessment the larger compensation redesign. Wilson Learning consultants recommended they implement a two-part assessment process designed around the critical competencies of the position. Wilson Learning further recommended the team consider a "two gate" approach for the assessment, where a candidate is required to pass successfully through an assessment comprised of two short behavioral simulations before proceeding to the second gate—the structured interview.

The entire selection process included:

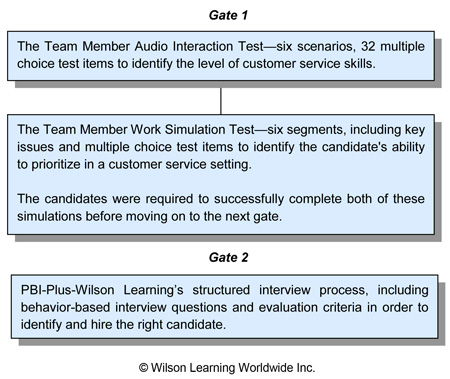

Gate 1

The Team Member Audio Interaction Test—six scenarios, 32 multiple choice test items to identify the level of customer service skills.

The Team Member Work Simulation Test—six segments, including key issues and multiple choice test items to identify the candidate's ability to prioritize in a customer service setting.

The candidates were required to successfully complete both of these simulations before moving on to the next gate.

Gate 2

PBI Plus—Wilson Learning's structured interview process, including behavior-based interview questions and evaluation criteria in order to identify and hire the right candidate.

During the computer-based audio interaction simulation, candidates listened to an audiotape where team members and customers provided background information on selected customer service problems, work unit issues, an employee's performance appraisal, etc. The audiotape then provided a series of multiple choice questions. At the end of each question, there was an eight-second delay in the audiotape for the candidate to select his or her answer and enter the response into a PC.

The second simulation was the Team Member Work Simulation Test. This automated in-basket-style simulation provided background material for selected customer service and work unit situations, which the candidates read and then responded to by answering multiple choice questions on a PC. The total duration of the first two simulations was approximately two hours.

The candidate's score for the first two simulations was tabulated and combined by a Microsoft Excel-based scoring model designed by Wilson Learning. After determining if the candidate's score was above the cut-off score that had been established, he or she was invited back for a PBI Plus interview—Wilson Learning's behavioral interview process. This process was tailored precisely to the team member position.

The PBI Plus interview segment of the assessment process was conducted by at least two trained individuals and was based on the situation, action, outcome (SAO) interviewing model. It was designed with an initial open-ended question for each of the competencies (total of eight) and a series of follow-up, probing questions to each initial question. The questions were designed to get specific behavioral information from a candidate on how he or she handled a specific situation that related directly to a critical job competency. The interviews each lasted approximately 45 minutes to an hour. The interviews with candidates who were not existing employees took 15 to 20 minutes longer because interviewers wanted to get to know each candidate and get some idea of the candidate's background and work experience prior to beginning the interview, and the external applicants had numerous questions of the interviewers.

After each interview, the interviewers reviewed the candidate's responses, reached consensus on a rating for each competency (using criteria that describe what is representative of an "above expectations," "at expectations," and "below expectations" response), and recorded their rating on an interview rating document. The data from the interview rating document was subsequently entered into the PC-based scoring model. The PC provided a report showing the candidate's score on each simulation and an overall composite score. Based on the composite score, a selection decision was made and communicated to the candidate.

For existing employees who went through the assessment process, and external candidates who were offered and who accepted employment with the organization, managers could utilize detailed feedback reports to discuss with each individual his or her strengths and developmental needs, from which competency development and learning plans could be initiated. These plans tied directly to the organization's new performance management system.

The bottom-line result is a controlled and rational process of organizational transformation.

The assessment process designed for the organization was integrated into a multi-tiered selection process for customer service personnel. The process included a résumé/application review, a detailed telephone interview, an initial on-site interview prior to assessment, and an in-depth pre-employment academic and criminal check after assessment and prior to extension of an employment offer.

The assessment process itself was designed to be conducted without outside assessors and interviewers. (Wilson Learning trained internal personnel in the full range of uses and implementations for the system.) The process was suitable for use with internal and external candidates.

First implemented in October 1994, the process has been utilized for all selections and hires made for the organization's new customer service center (in excess of 200 selections). Managers and team leaders feel the individuals selected through this process are fully integrating themselves into the new culture and are providing exemplary service to customers. Employees perceive the selection process to be objective, fair, consistent, and unbiased.

The bottom-line result is a controlled and rational process of organizational transformation. This organization has successfully developed and implemented an innovative selection tool, which is a key reason for its success in transforming a bureaucratic field customer service organization of 400-plus employees in multiple locations into a customer-focused, flexible, and team-based customer service organization of 270 employees. The company is located on one site now, reducing annual corporate operating expenses by six million dollars, six percent of its expense base. By any standard, that's an exceptional return on investment.

THE ASSESSMENT LINK BETWEEN STRATEGY AND HUMAN RESOURCES

Companies are taking a good hard look at the development of strategies and organizational restructuring to carry them into the future. More than ever, the strategic intent must be closely tied to the organization's capacity to carry it out. This ability is no longer painted in broad brush-strokes, but rather for hypercompetitive organizations it is a matter of great precision, as we have seen in the previous examples. Transformation results from the systematic and rational allocation of resources against a competitive goal. Selection and measurement technology allows a company to see where it is—diagnose values, strengths, and skill gaps among existing employees and potential new employees to create a workforce capable of seizing the competitive initiative. Traditional approaches to hiring, promoting, and evaluating employees based on an industrial age approach are no more successful in the information age than the hierarchical structures of the turn of the century were. The new strategies and corporate visions created by the hypercompetitive companies of today need to be supported by workforces that have been selected and developed in tune with those strategies and visions, synchronized with the pace of hypercompetition.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

If you would like more information regarding Wilson Learning's Assessment Offerings, call 1.800.328.7937, or contact us at Wilson Learning Corporation, 8000 W 78th Street, Suite 200, Minneapolis, MN 55439.

BENEFITS OF WILSON LEARNING’S ASSESSMENT MEASUREMENT OFFERINGS

While the broad benefits of using a behavioral approach to assessment are well documented, Wilson Learning's specific differentiation in this field is worth noting:

- Computerization of job analysis results are available in a versatile database.

- Analysis research is quick and to the point for building custom interviewing and assessment instruments.

- Research is developed rapidly on organizational core competencies.

- PBI structures and standardizes the hiring interview, turning it into a powerful tool for identifying and bringing aboard the right people for the right job, and the trained interviewers become better interviewers for all jobs in the process.

- PBI can be easily blended with Wilson Learning's computerized assessment center into a single selection tool, providing a single detailed final report valuable for developmental feedback to the candidate.

- Wilson Learning invented the computerized assessment center and it remains unique and powerful among its competitors. Final reports are available within 24 hours after the assessment center is completed.

- Wilson Learning's assessment services division continues to provide assessment centers to clients, saving them the necessity to train assessors, role players, and administrators.

- Wilson Learning's assessment services division can implement such an assessment within two weeks of notification of the need.

- Wilson Learning's accruing experience in the development of whole selection systems has made it an industry leader. The key to this is designing a system that is appropriate to the size of the task, which requires a level of effort on the part of the hiring organization that is appropriate to the importance of the job.

- Wilson Learning has a variety of custom 360 degree instruments, appropriate for virtually any level of implementation and size of survey population. Once again, Wilson Learning's hallmark in this area is speed and value.

To learn more, contact Wilson Learning at 1.800.328.7937 or complete the online form.

Please complete this form to download Assessment Technology in The Age of Hypercompetition (Point of View Paper).

Please complete this form to download Assessment Technology in The Age of Hypercompetition (Point of View Paper).